I almost missed the grand finale of this expedition. Forced by a passport problem to start the journey home suddenly and unprepared, I was sitting in Münster at home, my husband and round-the-world companion was still on the ship heading for Cape Town and I was waiting for my new passport. It arrived and with it the decision to return and join our team across the Atlantic. This happened at the beginning of May, when the weather had calmed down a bit. We are still many thousands of nautical miles away from home and it will take us eight days from Cape Town to St. Helena. I have to get used to long crossings again and get used to the movement of the waves. Because that’s how it feels, full of momentum, with wind from behind and waves, as if we were dancing towards our destination.

After two years and seven months, we’re heading back to the Mediterranean

Shortly before we arrive, we cross the Greenwich Meridian from east to west and have officially driven once around the world. I realize that we have now been on the road for two years and seven months. It certainly doesn’t feel like it and yet it is a long time. I am full of gratitude for this wonderful experience and the reliable technology that made it possible. My thoughts don’t just wander back to my own experiences, but suddenly I think about the circumnavigators of history. How long did it take the first circumnavigators to cover the distance in the days when there was no Panama Canal?

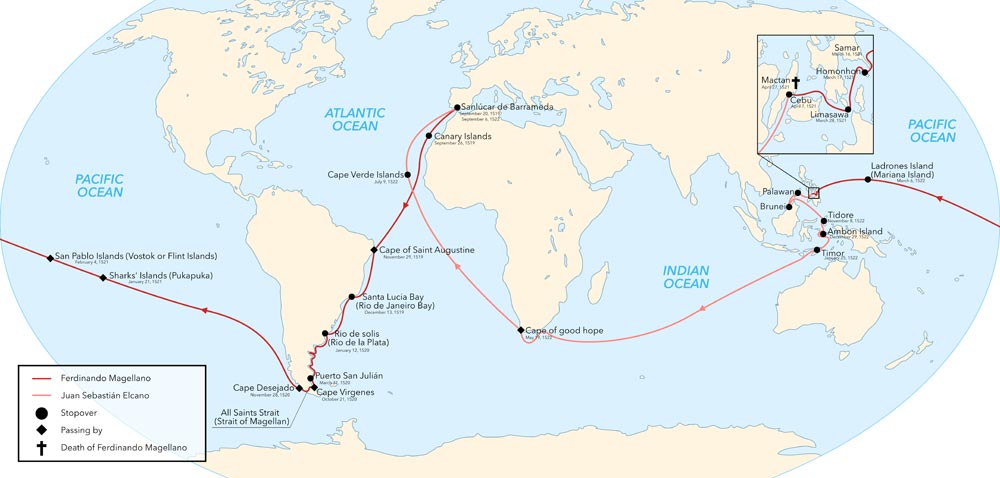

It is astonishing that the first circumnavigator Ferdinand Magellan, the discoverer of the Strait of Magellan in the south of the Latin American continent, also “only” needed three years. He set off in 1519 and his aim was to cover the route to the west and the Spice Islands to find them. He did, but he was killed on the return voyage to the Philippines and his officer Juan Sebastián Elcano completed the expedition in 1522. Of the five ships, only one, the Victoria, returned to Spain with 18 men and he received the honor of being the first to have sailed around the world.

Less than sixty years later, Sir Francis Drake set off on his voyage from England. He also sailed through the newly discovered Strait of Magellan, but then had a few problems getting away from Cape Horn. Once he had managed to do so, he sailed almost the entire west coast of Latin America and America as far as Vancouver. In between, he raided a few Spanish ships that wanted to make their way home with the gold stolen from the Incas, robbed a few coastal towns and then took the route through the Pacific to Europe, like Elcano.

The North-West Passage was not yet passable. Later, many explorers, such as Sir John Franklin in 1845, made tragic and unsuccessful attempts. It was not until 1903 that Roald Amundsen succeeded in crossing it completely. Drake had to sail back to Europe via the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic and also took three years to circumnavigate the globe. He returned to England with a ship full of treasure, which Queen Elizabeth was delighted to receive. He was knighted and was a made man. But once a sailor, always a sailor. Both he and Elcano lost their lives a year later during further exploratory voyages.

We were also forced to sail around the Cape of Good Hope, even though the Suez Canal has existed since 1869. Another miracle of engineering, if it weren’t for the Hutis, the Americans, the Isrealis, the Saudis, the Iranians, etc. The world and our insurance company prevented the passage. At least we were able to enjoy the blessing of modern navigation technology, engines, stabilizers and refrigerators on our round-the-world trip. It was not necessarily full of hardship, but no less adventurous, because the seas still harbor dangers and the vagaries of the weather are becoming less predictable due to climate change. Technology can go on strike and it takes people to move this venture forward. It takes resilience to endure slowness, loneliness and uncertainty. Enthusiasm to want to discover new things, which can sometimes turn into despondency if the organization on the ground is not up to the task.

The feeling of having overcome and made it releases strong forces

However, before we tackle the long journey back across the Atlantic, we make a stopover on St. Helena. This rugged rock in the Atlantic, once Napoleon’s place of exile, is a welcome change on the long journey home. There are 4,300 people living here, so everyone knows everyone else and on our island tour we are constantly greeted and waved at. The people of St. Helens are very friendly. Jacob’s Ladder, a 699-step staircase that was once used to supply the bastion on top of the cliffs, is now a tourist attraction and a welcome fitness session for tired boaters‘ legs.

We take a look at the house where Napoleon spent his time in exile until his death. It may not be magnificent, but it is very cozy. He may have been sent to the end of the world, in the middle of a small rock in the Atlantic, but he was surrounded by well-meaning people and a certain level of comfort. We eat at Anna’s, the hot spot for circumnavigators and Atlantic crossers, as evidenced by numerous photos, posters and pennants. Anna has lived in Germany for over twenty years – yes, the world is that small, and not just on St. Helena.

We are still underway, have gone passed Cape Verde and are currently heading to Madeira and from there to Barcelona, where we hope to arrive safely in June with a boat full of our personal treasures.

What a delightful read! Its fascinating to contrast our modern, technologically cushioned voyage with the sheer grit of historical circumnavigators. Magellan and Drake, facing literal life-or-death struggles with far less than a refrigerator, still managed in about three years – impressive! While we enjoy the blessing of modern navigation, it seems our insurance company and the world at large had other plans, forcing a detour via the rugged rock of St. Helena. Its a humorous reminder that even with all our advancements, the world (and our engines) can still be unpredictable. The journey home across the Atlantic awaits, full of potential waves and the dance of the ship. Long may she sail, albeit with a reliable skipper and a functioning engine!